manual clock

Manual clocks, originating in 13th-century Europe, represent a pivotal shift in timekeeping, utilizing weights or springs for power and intricate mechanisms for accuracy.

What is a Manual Clock?

A manual clock is a mechanical timekeeping device powered by either a weight or a coiled spring, requiring periodic manual winding to maintain operation. Unlike modern electronic clocks, these timepieces rely on a complex interplay of gears and escapements to measure and display time.

Early examples, appearing in 14th-century Italy, were large, weight-driven turret clocks, primarily striking the hours without hands or dials; Later developments included smaller, more portable designs like bracket and longcase clocks. The core components – a power source, regulator, and escapement – work in harmony to provide relatively accurate timekeeping, a significant advancement over earlier methods like sundials or water clocks.

Historical Significance of Manual Clocks

Manual clocks dramatically reshaped societal structures, moving beyond simply marking time to regulating daily life, trade, and the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. Their emergence in the 13th and 14th centuries, influenced by Islamic and Chinese horological advancements, marked a turning point in precision and standardization.

Before manual clocks, time was often a localized and imprecise concept. These mechanical marvels enabled coordinated activities, facilitated commerce, and ultimately, fueled innovation. The ability to accurately measure time was crucial for navigation, manufacturing, and the organization of labor, laying the groundwork for modern technological progress and a more structured world.

The Early History of Mechanical Timekeeping

Mechanical timekeeping began around the 13th century in Italy and Germany, evolving from ancient concepts and incorporating influences from Islamic and Chinese clock designs.

Origins in Ancient Civilizations

The quest to measure time stretches back millennia, with early civilizations employing ingenious methods before the advent of mechanical clocks. Ancient Egyptians utilized sundials and water clocks – clepsydras – to divide the day, while advancements continued in Greece and Rome. However, these relied on observing shadows or the consistent flow of water, lacking the precision and independence of mechanical devices.

Crucially, knowledge transfer played a vital role. Trade expeditions during the early Renaissance introduced European inventors to sophisticated Islamic clocks and intricate Chinese water clocks. These designs, showcasing advanced engineering, provided a foundation upon which Europeans built, ultimately leading to the development of the first mechanical timekeepers around the year 1300. These early influences were essential stepping stones.

Islamic and Chinese Influences on European Clockmaking

The development of mechanical clocks in Europe wasn’t a purely isolated invention; it was significantly shaped by knowledge acquired from other cultures. During the 12th and 13th centuries, trade expeditions of the early Renaissance brought invaluable insights from the Islamic world and China. Islamic clockmakers had created sophisticated water clocks with complex gearing, demonstrating advanced mechanical understanding.

Simultaneously, Chinese intricate water clocks showcased remarkable precision and innovative designs. These examples provided European inventors with a crucial basis for their own experiments and improvements. By studying and adapting these existing technologies, European artisans were able to build upon established principles, accelerating the progress towards creating the first functional mechanical clocks.

The First Mechanical Clocks (13th-14th Century)

The earliest mechanical clocks emerged around the year 1300, primarily in the region spanning northern Italy to southern Germany. These weren’t the precise timekeepers we know today; they were large, weight-driven machines installed in towers – what we now call turret clocks. A defining characteristic of these initial devices was their simplicity: they only struck the hours, lacking the hands or dials to display the time continuously.

Despite their limitations, these clocks represented a monumental leap forward in timekeeping technology. The fundamental components – a power source, a regulator, and an escapement – were established, laying the groundwork for future innovations and refinements in clockmaking.

Verge-and-Foliot Escapement: The Initial Mechanism

The verge-and-foliot escapement was the foundational mechanism powering the first mechanical clocks of the 13th and 14th centuries. This system utilized a verge – a pivoting bar with two pallets – interacting with a foliot, a horizontal balance wheel. The foliot’s oscillation, regulated by its weight and shape, controlled the release of the clock’s power, provided by a falling weight or wound spring.

While innovative for its time, the verge-and-foliot was relatively inaccurate. Its performance was significantly affected by temperature changes and friction, leading to considerable timekeeping errors. Nevertheless, it remained the dominant escapement for several centuries, paving the way for more precise mechanisms.

Key Components of a Manual Clock

Essential components include a power source (weights or springs), a regulator controlling time, an escapement releasing power, and gears transmitting motion precisely.

The Power Source: Weights and Springs

Early manual clocks predominantly relied on falling weights as their power source. Suspended from a cord wrapped around a drum, the descending weight’s potential energy drove the clock’s mechanism. These were substantial, necessitating large clock cases to accommodate the weight’s travel.

Later, springs emerged as a more compact alternative. Wound tightly, a spring gradually released its stored energy, powering the clock’s movement. This innovation allowed for smaller clock designs, like bracket and mantel clocks. The development of improved spring technology was crucial for enhancing the reliability and portability of manual timekeeping devices, marking a significant advancement in horological engineering.

The Regulator: Controlling the Time

The regulator in a manual clock is the component responsible for controlling the rate at which time passes, ensuring consistent and measurable intervals. Initially, the verge-and-foliot escapement served this purpose, oscillating back and forth to regulate the release of power.

However, this system was prone to inaccuracies. Christian Huygens’s pendulum, introduced in 1656, dramatically improved precision by utilizing the consistent swing of a pendulum. Subsequently, the balance wheel became a common regulator, offering greater portability and resilience to disturbances, crucial for smaller, more mobile timepieces.

The Escapement: Releasing Power Incrementally

The escapement is a critical mechanism within a manual clock, meticulously regulating the release of power from the power source – whether weights or springs – in controlled increments. The earliest form, the verge-and-foliot escapement, utilized a verge connected to the foliot balance, intermittently stopping and releasing the gear train.

This allowed for the characteristic ‘ticking’ sound. Later advancements refined this process, improving accuracy and efficiency. The escapement’s function is to translate the continuous force of the power source into discrete steps, marking equal intervals of time and driving the clock’s hands forward.

Gears and Wheels: Transmitting Motion

Gears and wheels form the intricate network within a manual clock, responsible for transmitting the regulated power from the escapement to the clock’s display. These precisely cut components work in harmony, reducing the speed of the power source to drive the hour, minute, and sometimes second hands at the correct rates.

Different gear ratios determine the speed of each hand, ensuring accurate timekeeping. The arrangement and quality of these gears are crucial for the clock’s overall performance and longevity, showcasing the ingenuity of early clockmakers.

Evolution of Manual Clock Technology

Technological advancements, like Huygens’ pendulum in 1656 and improved spring mechanisms, dramatically increased the precision and reliability of manual clocks over centuries.

The Pendulum Clock (1656) and Huygens’ Contribution

Christian Huygens’ invention of the pendulum clock in 1656 marked a monumental leap forward in timekeeping accuracy. Prior mechanical clocks, reliant on the verge-and-foliot escapement, suffered from significant inaccuracies. Huygens realized the consistent, isochronous swing of a pendulum could serve as a superior regulator.

His design utilized a pendulum suspended from a fixed point, controlling the release of the clock’s power through an improved escapement mechanism. This innovation drastically reduced errors, offering a level of precision previously unattainable. The pendulum clock quickly became the standard for accurate timekeeping, influencing clock design for centuries and paving the way for further refinements in mechanical timekeeping technology.

Improvements in Spring Technology

Early manual clocks primarily utilized falling weights for power, limiting their size and portability. The development and refinement of mainspring technology were crucial for creating smaller, more convenient timepieces. Initially, springs were often made of iron, prone to breakage and inconsistent performance.

Over time, advancements in metallurgy led to the use of stronger, more durable materials like steel. Improved spring tempering techniques further enhanced their elasticity and longevity. These innovations allowed for the creation of increasingly compact and reliable clocks, ultimately leading to the development of portable clocks like bracket and mantel clocks, expanding access to accurate timekeeping.

The Development of the Balance Wheel

As spring-driven clocks gained prominence, the need for a more precise regulator than the verge-and-foliot became apparent. The balance wheel, initially appearing in the 15th century but significantly refined later, offered a superior solution. This oscillating wheel, coupled with a hairspring, provided a consistent and controlled rate of oscillation, dramatically improving timekeeping accuracy.

Early balance wheels were relatively crude, but continuous improvements in design and materials – including the introduction of temperature-compensating alloys – led to increasingly reliable performance. The balance wheel became a cornerstone of portable clock mechanisms, enabling the creation of accurate watches and smaller clocks.

Types of Manual Clocks

Manual clocks diversified into turret, bracket, longcase (grandfather), and mantel clocks, each serving distinct purposes and showcasing varying levels of craftsmanship and size.

Turret Clocks (Tower Clocks)

Turret clocks, also known as tower clocks, represent the earliest widespread form of mechanical timekeeping. These substantial, weight-driven machines were initially installed within the towers of churches, cathedrals, and public buildings during the 13th and 14th centuries. Remarkably, these pioneering clocks primarily functioned to strike the hours, lacking the hands or dials we associate with modern timepieces.

Their immense size and complexity necessitated significant engineering expertise for construction and maintenance. The weight, descending gradually, provided the power, while an escapement mechanism regulated its release. These clocks weren’t about individual time-telling, but rather announcing the canonical hours for religious observance and structuring communal life. They were a public declaration of time, a shared experience for the community.

Bracket Clocks

Bracket clocks emerged as a refined and portable evolution of earlier manual clock designs, gaining prominence in the 17th and 18th centuries. Unlike the large turret clocks, these were designed for domestic settings, typically placed upon ornate wooden brackets – hence the name. They featured fully enclosed cases, often crafted from beautiful woods like walnut or mahogany, protecting the delicate movement within.

Driven by springs rather than weights, bracket clocks offered greater convenience and portability. Their movements incorporated advancements like the pendulum and balance wheel, enhancing accuracy. They became status symbols, showcasing the owner’s wealth and appreciation for craftsmanship, representing a significant step towards personalized timekeeping.

Longcase Clocks (Grandfather Clocks)

Longcase clocks, popularly known as grandfather clocks, arose in the late 17th century as a direct response to the pendulum’s requirement for a long, stable swing. These imposing timepieces feature a tall wooden case – often oak, walnut, or cherry – housing the clock’s movement and a long pendulum. The extended case allowed for a longer pendulum, significantly improving timekeeping accuracy compared to earlier designs.

Driven by weights suspended within the case, longcase clocks became a central feature in many homes, not just for telling time but also as a statement of prosperity and refined taste. Their elaborate dials and cases often showcased intricate marquetry and decorative elements.

Mantel Clocks

Mantel clocks emerged as a more compact and accessible alternative to the larger longcase and bracket clocks, designed specifically for placement on mantelshelves or similar surfaces. Popularized in the 18th and 19th centuries, these clocks typically utilized spring-driven movements, making them more convenient for homes lacking space for weight-driven mechanisms.

Their cases were often beautifully decorated, reflecting various stylistic trends like Chippendale, Victorian, and Art Deco. Mantel clocks became a common household item, offering a blend of functionality and aesthetic appeal. They represented a shift towards more portable and decorative timekeeping solutions.

The Impact of Manual Clocks on Society

Manual clocks revolutionized daily life, trade, and commerce by providing a standardized measure of time, fostering precision and structure within communities.

Timekeeping and Daily Life

Manual clocks dramatically altered the rhythm of daily life, moving societies away from relying on imprecise natural cues like sunrise and sunset. Before their advent, activities were loosely organized around these natural phenomena. The introduction of mechanical timekeeping, initially through large turret clocks and later with smaller domestic versions, brought a newfound structure to work and leisure.

Communities began to synchronize activities, from market opening hours to religious observances, based on the clock’s consistent measurement. This standardization fostered greater efficiency and coordination. Individuals, too, adjusted their routines, becoming more aware of and accountable to scheduled time. The very concept of punctuality gained importance, influencing social interactions and professional expectations.

Influence on Trade and Commerce

Manual clocks profoundly impacted the burgeoning world of trade and commerce during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Accurate timekeeping enabled merchants to schedule meetings, coordinate shipments, and manage transactions with greater precision. The standardization of time facilitated long-distance trade, as merchants could reliably predict arrival times and synchronize activities across different locations.

Financial institutions, such as banks, benefited immensely from the ability to track time accurately, improving record-keeping and facilitating complex financial operations. The increased efficiency in commercial activities spurred economic growth and contributed to the rise of a merchant class. Contracts and agreements became more enforceable, fostering trust and stability in the marketplace.

Role in the Industrial Revolution

Manual clocks, though predating the full force of the Industrial Revolution, laid a crucial foundation for its eventual success. The demand for precise timekeeping grew exponentially as factories emerged and required coordinated work schedules. Accurate clocks enabled factory owners to manage labor, optimize production processes, and ensure consistent output.

The discipline of time became ingrained in the industrial workforce, fostering a culture of punctuality and efficiency. This newfound precision extended beyond the factory floor, influencing transportation networks – like railways – and contributing to the overall organization of industrial society. The very concept of standardized time, essential for industrial coordination, owes its origins to the advancements in mechanical timekeeping.

The Decline and Resurgence of Manual Clocks

Manual clocks faced decline with the 1930s’ quartz clock rise, but experienced a resurgence as valued collectibles and admired art objects showcasing craftsmanship.

The Rise of Quartz Clocks in the 20th Century

The 20th century witnessed a dramatic shift in timekeeping dominance with the emergence of quartz clocks. Introduced in the 1930s, these clocks quickly gained popularity due to their superior accuracy and significantly lower production costs compared to traditional manual clocks.

Quartz clocks utilize the piezoelectric properties of quartz crystals to create a precise and stable frequency, resulting in remarkably accurate time measurement. This contrasted sharply with the inherent variability of mechanical movements found in manual clocks, which were susceptible to temperature changes and required regular adjustments.

The affordability and reliability of quartz clocks led to their widespread adoption, gradually diminishing the demand for meticulously crafted manual clocks for everyday use. While manual clocks didn’t disappear, their role transitioned from primary timekeepers to objects of historical interest and horological artistry.

Manual Clocks as Collectibles and Art Objects

Despite the rise of quartz technology, manual clocks haven’t faded into obscurity. Instead, they’ve experienced a resurgence as highly sought-after collectibles and admired art objects. Their intricate mechanisms, showcasing centuries of engineering and craftsmanship, appeal to enthusiasts and collectors worldwide.

The beauty of their design, often featuring ornate cases and meticulously decorated movements, elevates manual clocks beyond mere timekeeping devices. Each clock represents a unique piece of history, reflecting the aesthetic sensibilities and technological capabilities of its era.

Restored manual clocks are frequently displayed as statement pieces, embodying a connection to the past and a celebration of mechanical artistry. Their enduring appeal lies in their tangible quality and the captivating rhythm of their moving parts.

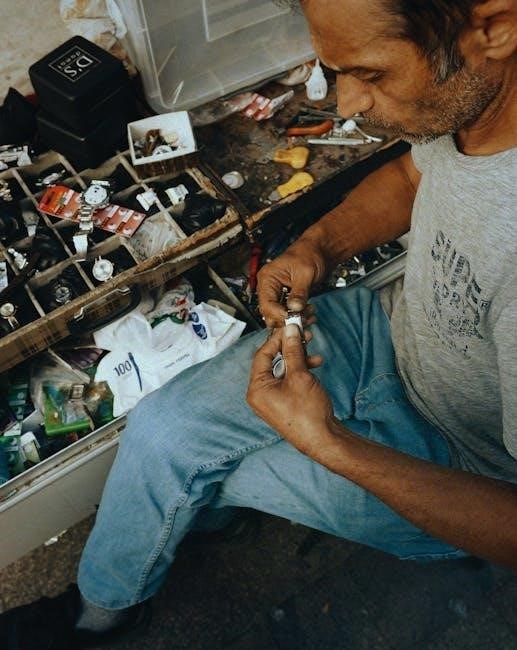

Maintaining and Repairing Manual Clocks

Regular maintenance, including cleaning and oiling, is crucial for manual clocks; qualified clockmakers can address complex repairs and ensure continued accuracy.

Basic Maintenance Procedures

Consistent, gentle care extends the life of your manual clock. Dust accumulation is a primary concern; use a soft brush to carefully remove it from the movement and case, avoiding any forceful actions. Periodically, inspect the pendulum or balance wheel for obstructions, ensuring free and even swings. Avoid over-winding, as this can strain the mainspring.

Lubrication is vital, but best left to professionals – improper oils can cause damage. Regularly check the clock’s levelness; an uneven surface impacts accuracy. Listen for unusual noises, which may indicate a need for professional attention. Simple cleaning and observation can prevent minor issues from escalating into costly repairs, preserving the clock’s functionality and value for generations.

Common Repairs and Troubleshooting

Manual clocks often require attention to the escapement, a frequent source of issues causing erratic timekeeping or complete stoppage. Broken mainsprings are also common, necessitating replacement by a skilled clockmaker. Gear wear, resulting from friction over time, can lead to slippage and inaccurate readings. Inspecting the pendulum suspension spring for damage is crucial, as a broken spring halts the clock.

Troubleshooting often begins with ensuring proper winding and level placement. If the clock consistently loses time, the regulator may need adjustment. Persistent issues demand professional diagnosis; attempting complex repairs without expertise can inflict further damage. Regular maintenance minimizes the need for extensive, costly interventions.

Finding a Qualified Clockmaker

Locating a skilled clockmaker is vital for preserving your manual clock’s functionality and value. Seek professionals with demonstrable experience in mechanical timepieces, ideally those specializing in antique clocks. Referrals from fellow collectors or local historical societies are excellent starting points. Certification from organizations like the British Horological Institute signifies a commitment to quality.

Inquire about their experience with your clock’s specific type – turret, bracket, longcase, or mantel. A reputable clockmaker will offer transparent estimates and detailed explanations of required repairs. Avoid individuals who propose quick fixes without thorough diagnosis; patience and precision are paramount in clock restoration.

The Future of Manual Clocks

Manual clocks endure through craftsmanship appreciation, blending with modern designs, and symbolizing heritage—a testament to enduring engineering and timeless aesthetic appeal.

Continued Appreciation for Craftsmanship

Manual clocks represent a remarkable legacy of human ingenuity and skilled artistry. Unlike mass-produced, digital timepieces, each manual clock embodies countless hours of meticulous handwork, from the delicate engraving of gears to the precise assembly of intricate movements. This dedication to craftsmanship fosters a deep appreciation among collectors and enthusiasts.

The resurgence of interest isn’t merely nostalgic; it’s a recognition of quality and enduring value. Individuals increasingly seek objects with a story, a tangible connection to the past, and a demonstration of exceptional skill. The mechanical complexity and aesthetic beauty of these clocks continue to captivate, ensuring their relevance in a world dominated by disposable technology. This enduring appeal guarantees the preservation of traditional clockmaking techniques for generations to come.

Integration with Modern Design

Manual clocks are experiencing a fascinating blend with contemporary aesthetics, moving beyond purely traditional presentations. Designers are incorporating visible movements into minimalist frameworks, showcasing the intricate mechanics as a central design element. This fusion creates striking focal points within modern interiors, offering a captivating contrast between old-world craftsmanship and sleek, current styles.

Furthermore, innovative materials – beyond traditional wood and brass – are being utilized, such as acrylic, glass, and even carbon fiber. This allows for unique visual effects and a reimagining of classic clock forms. The result is a renewed relevance for manual clocks, appealing to a broader audience seeking both functionality and artistic expression within their living spaces.

Manual Clocks as Symbols of Heritage

Manual clocks transcend mere timekeeping devices; they embody centuries of human ingenuity and mechanical evolution. Originating in the 13th and 14th centuries, these clocks represent a tangible link to the past, showcasing the skills of early clockmakers and the dawn of precision engineering. Owning a manual clock is often a conscious decision to preserve and celebrate this rich history.

They serve as reminders of a slower, more deliberate pace of life, contrasting with the digital immediacy of modern technology. These clocks are frequently passed down through generations, becoming cherished family heirlooms and symbols of enduring legacy, connecting individuals to their ancestors and cultural roots.